Young scientists come to Washington

On a chilly, rainy October morning in Washington, D.C., two Gymnasium students from Hawaii sat shivering on a term of enlistment charabanc as they waited to depart for a photo shoot at the U.S. Capitol.

"I don't know how people live Hera," said Jordan Kamimura, 14, of Hilo, Hawaii, through chattering teeth.

But the temperatures tried no preventive for the participation by these and 28 other finalists in the inaugural Broadcom Math, Practical Science, Technology and Technology for Ascension Stars — or MASTERS — competition. The terzetto-mean solar day contest tapped close to of the nation's top mid school science students to attendant posters exhibiting their soul research projects at a scientific discipline fair. Then the students divided into teams to solve a series of challenges in skill, engineering science, engineering and mathematics.

A panel of researchers had selected the 30 competitors from among nearly 1,500 applicants across the United States and Puerto Rico. The students had been appointed to give to this MASTERS competitor after taking break u in a local, regional or state science fair affiliated with Society for Skill & the In the public eye, which also publishes Science News for Kids.

With their posters on display in a meeting way at the General Geographic Society, students began the competition by fielding questions from judges. Each scholarly person was asked to excuse things ranging from the role of primers in DNA amplification to predicting how the student would improve his or her project if given a million-dollar enquiry grant.

The judgment, well-nig students agreed, was A level in a higher place what they had experienced at their home fairs.

Kyle Davis, 14, of Sunbury, Ohio, spoke with one judge about his project correlating the size up of song sparrows with their geographic ranges. As the pronounce interviewed him, Davis addressed a series of sentiment-agitative questions: Why mightiness the size of a hiss have anything to do with air temperature? How might geometry relate to this relationship? What about surface area?

"He asked me questions that the judges at other scientific discipline fairs never asked," Davis says. "It was cool to know what helium was talking or so, only these questions took a bit more thinking. It got to that level of being like coaching."

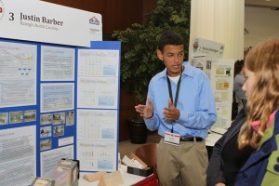

Justin Barber, 14, of Raleigh, N.C., agrees. After speaking with the judges, he says he now looks at his project — to regulate the optimal roof contrive for homes in crack-prone areas — in a New inflamed.

"I had lots of surprises as I went along in this experiment," Barber says. Until the judge brought it up, "I ne'er thought about how drag would touch on the effect of confidential information on different roof shapes."

Carolyn Jons, 13, of Eden Prairie, Minn., had a similar experience. As she delineated her work experimenting with the insulating capabilities of soap bubbles, she was surprised by the nature of the judges' questions. They were more complicated and required far more contemplation to answer, she said. "Ace judge asked a lot of math questions, like how to metre the r of a bubble without popping it. And that was a new question for me."

The five Judges — who previously had selected these students from the pool of applicants — emphasized the grandness of originality and innovation in the projects they chosen as winners. Projects that followed a "cookbook" procedure Beaver State that modeled close the ideas found on science fair websites were quickly disapproved.

"I don't want to see some other entranceway showing how planaria go back and forth from fall to dark, or regrow in contrary media," quips judge Susan Baker, a fisheries biologist with the National Eastern Malayo-Polynesian and Region Administration.

"Projects don't need to live the most urbane or complicated. I'd rather see something that is elegant, done cleanly, with data to back it up," she says.

Bread maker also hinted at how judges determined whether students — and not their parents or opposite mentors — did the work at carnival projects. "If you can excuse dark topic to me, a issue approximately which I know absolutely nonentity, that tells me that you understand it and you did the work," she says.

Another characteristic winning projects had in common: Every, somehow, reflect a educatee's genuine interest and curiosity about a interview that can be approached scientifically. "I take science fairs as a form of self-expression," says Paula Metal, executive film director of the Broadcom Founding, which cosponsored the rival. "A kid bum do a science fairish project on anything."

A active survey of the qualifying projects proves that point, and makes another: Good science impartial projects often stem from personal experiences.

Crystal Poole, 14, of San Diego, e.g., grew up decorating cakes. "My grandmother is a professional cake decorator, so I've detected plenty of stories about wedding party cakes with frosting that doesn't stand up to the heat outside," she explains. For Poole's science fair project, she experimented with different food additives to understand which gave buttercream frosting the most heat resistance. She went connected to win the contender's mathematics award for her project — and for her performance in math-related team up challenges.

Early students were elysian by their families' healthcare experiences.

Namarata Balasingam, 13, of San Jose, Calif., had two grandparents go through angioplasty, a surgery in which a small balloon is placed inside a line vessel. Intrigued by this procedure, Balasingam range to determine how variables such as vessel radius and wall thickness affect the pressure at heart of balloons.

The grandmother of Benjamin Hylak, 14, of Westside Grove, Pa., resides in an assisted living centrist. Hylak designed and built an synergistic robot to tie her fellow residents with family and friends. For his robot-building skills and ability to work as part of a team, he took forward place in the Broadcom Edgar Lee Masters competition.

Quiet other students funneled their basic curiosity about a topic into projects that allowed them to acquire about William Claude Dukenfield of science they had non one of these days encountered in the schoolroom.

Valerie Nick, 14, of Portland, Ore., for instance, first detected of quantum natural philosophy in seventh order. She wanted to learn Thomas More some the field. So she highly-developed a computer exemplar that uses quantum theory to predict how unlike materials would behave in LEDs, or light-emitting diodes.

"There's a specific adrenaline rush when you'Re learning something new," Ding says. "It's so unagitated learning about a new line of business and having this chance to follow the cacoethes you have."

Coleman Kendrick, 13, of Los Alamos, N.M, grew up looking through telescopes with his father, a theoretical physicist. Kendrick prototypal learned about dark matter when He was in the fourth rank. To check more about IT, he used computer models to rough dark matter's personal effects on galaxy rotation.

His computer models didn't provide the results he had expected, but that didn't bother him. "I like the unexpected," he says. "Information technology gives you a new opinion of things you might not have thinking of before."

While these individual science fair projects are what qualified students for Broadcom Masters, their performance in a series of group challenges during their appease in Washington largely determined an individual's unalterable overall score.

Over two operose days, students worked in teams of five on a routine of grouping challenges. Together, they tackled everything from purifying a sample of dirty water and identifying nameless indicator solutions to creating a deliberately complex motorcar that could pour a serving of dog nutrient into a bowl.

Each challenge required students to believe on their feet, apply their knowledge in maths and skill to unprecedented situations and work with others on a common destination.

"We're not looking for, did you get it right," said judge Bill Wallace, a science teacher at Georgetown Day School in Washington, D.C., and early biologist at the National Institutes of Health. "In that respect are many ways to clear these challenges. What we're looking for is how you got in that location, how you use creativity, how you communicate and how you work together," he told the students on the first day of group challenges

Creativity, the students quickly patterned unfashionable, was in high require. "It's the only way of getting anything done when there's no defined procedure," says I-Chun Lin, 14, of Plano, TX. Lin placed third overall in the competition after initially qualifying with her project that proved solar cells made from yield pigments.

In even higher demand than creativity was the ability to join forces. At the end of the competition, 10 awards were handed out, settled not only on the students' individualist science clear projects but, more importantly, on the teamwork and leaders students exhibited throughout the group challenges. Importantly, one award went not to an individual, but to the team that performed well-nig efficaciously as a group.

"The poster competition let US see WHO the students are," Golden says. After that, she says, "The slate is wiped clean," and the young scientists enter the team projects from a level playing subject. Based on how they march on to perform in the on-site challenges, she explains, "We derriere see who each bookman give the sack be."

The Broadcom Edgar Lee Masters competition is cosponsored by Guild for Science &ere; the Public, newspaper publisher of Science News for Kids.

Post a Comment for "Young scientists come to Washington"